Feeling Superstitious: The Scottish Play

It’s no secret that theatre people are a superstitious bunch. With the rich history of performing arts, it’s no wonder that traditions to ward away bad luck or even ghosts have been passed down through the centuries. This month, we’re uncovering the history of some of the most well-known – as well as specific to Shakespeare Theatre Company—superstitions in the theatre.

Daring to speak the name of Macbeth (yes, we said it) has a near universality. Across the world, theatre companies fear invoking a curse whose effects range from blown-out light bulbs to concussions to fatality. In British Sign Language, the sign for Macbeth is the sign for Scotland, censoring the name itself to the euphemism the Scottish play.

Macbeth and the superstition behind its name have had a long history, beginning with the context of its authorship. The primary reason for distrust in the title stemmed from its connection to witches and depiction of sorcery onstage. Shortly before Shakespeare took quill to paper to write the play, the newly crowned King James I renounced witchcraft within England. Decades prior, James’ executed mother, Mary, Queen of Scots, had a long fascination with the dark arts. In 1589, James also had a near-death experience while sailing from Scotland; his immediate blame for the storm was on witches and he called for a witch hunt in the coastal town of North Berwick. Ultimately, James’ hatred for anything associated with witchcraft compelled him to pen Daemonlogie as way to inspire further persecution of anyone believed to be associated with the craft.

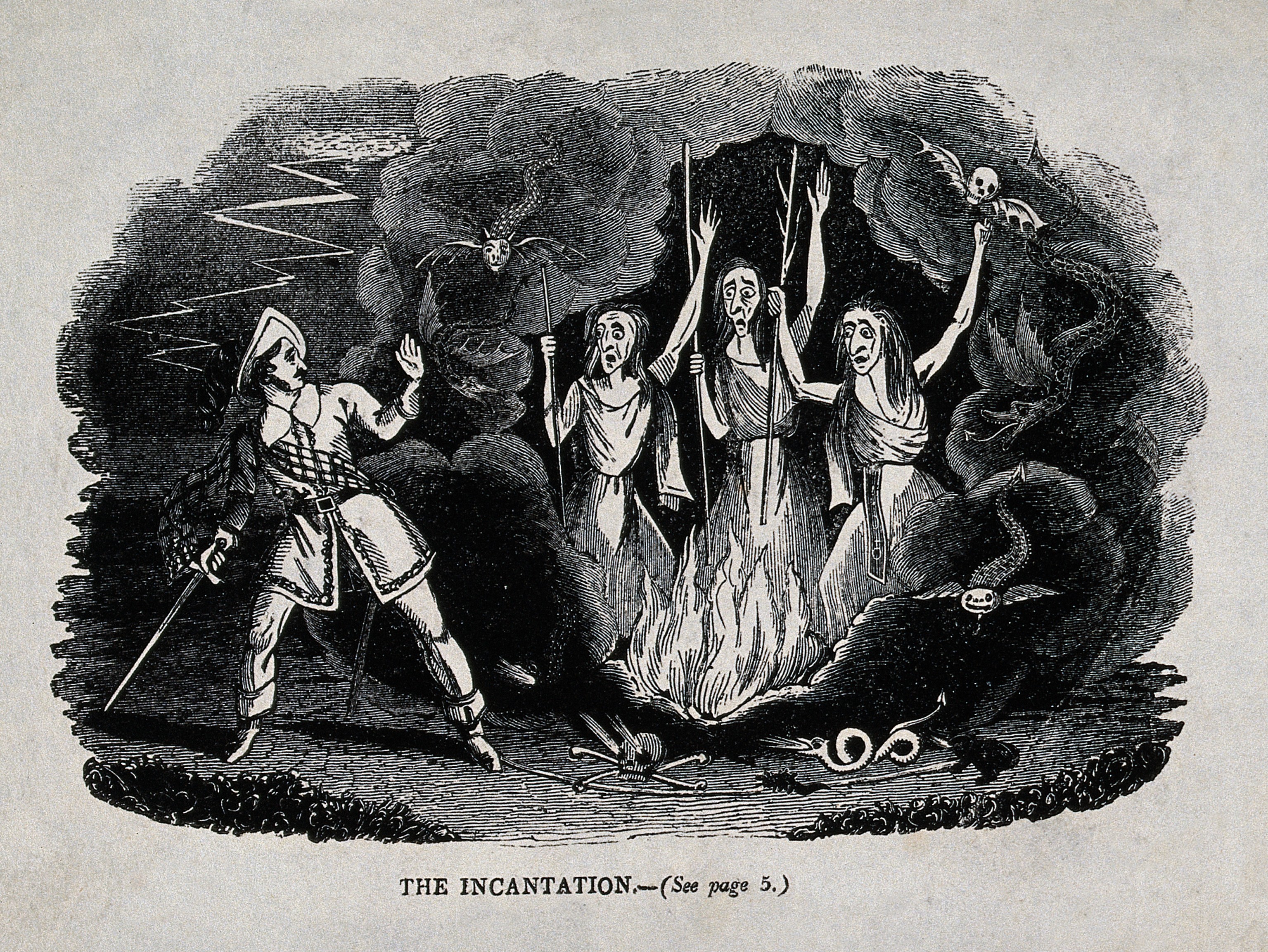

Shakespeare’s inclusion of the Weird Sisters was a bold move during this time. There are theories that the “toil and trouble” speech is a real spell stolen from real witches; others think that the spells in the play were incomplete—either way, it was originally believed that real witches were upset enough by this possible plagiarism to curse to play. The dialogue of the Weird Sisters is written in terameter, rather than the typical iambic pentameter, which already makes their curse stand out from the norm.

While the folklore behind the first-ever Lady Macbeth dying during a performance in 1606 is a myth created by disgruntled 19th-century critic and cartoonist Max Beerbohm, there are a disturbing number of incidents related to this particular play. In 1672, an actor playing Macbeth killed another actor when real weapons were used onstage rather than prop swords. In 1947, Harold Norman, who stated repeatedly that he did not believe in the curse, died while playing the title role. The Astor Place Riots were spurred by dueling performances of Macbeth by English actor William Macready and American actor Edwin Forrest and resulted in over 20 deaths and hundreds of injuries.

Perhaps the most infamous Macbeth production was in 1937 starring Laurence Olivier. The acclaimed actor was nearly hit by a falling stage weight and the director and actress portraying Lady Macbeth were nearly involved in a car crash prior to opening. Stage manager Lilian Baylis died during rehearsals and, during the postponed opening of the show weeks later, her portrait is rumored to have clattered off the wall. Finally, a real weapon used onstage slipped out of an actor’s hand, falling into the audience and resulting in a patron having a heart attack. As with all superstitions, these stories should be taken with a grain of salt. And it should be noted that statistics have a large part to play in these occurrences. Macbeth is one of the most popular works of Shakespeare and more productions create more opportunities for mishaps.

As with all good curses, there is a proper method to reverse it. If you have made the mistake of saying the dreaded play’s title on theatre grounds, run around the theatre (or spin in a circle three times), spit on the ground, and either curse or quote another of Shakespeare’s plays. Popular quotations for this include:

- “Angels and ministers of grace defend us!” –Hamlet, act I, scene 4

- “If we shadows have offended…” –A Midsummer Night’s Dream, act 5, scene 2

- “Fair thoughts and happy hours attend on you.” –The Merchant of Venice, act 3, scene 4